🔗 Shallow Fusion: Bridging Data Scarcity and AI Integration Challenges

COLLINS WESTNEDGE

AUGUST 26, 2025

Introduction

AI adoption and integration have become focal points in seemingly every earnings call, LinkedIn post, townhall and industry keynote. However, most of these conversations exist to highlight revenue potential, promote products and services, or bolster positive consumer sentiment, which is likely why they tend to gloss over or abstract away the technical challenges that stand in the way of effective adoption. One of the fundamental challenges is the gap between available data and the data needed for a domain-specific task.

Consider, for example, applying a large generalist model to a highly specialized task that barely surfaces in its pretraining data if at all. For the generalist model to succeed, it must first grasp dense company prospectuses, specialized jargon, and the nuances of the business problem itself. To address this gap companies often resort to standard recipes, e.g., “exciting” the right activations through few-shot examples, dumping streams of internal documents into the model’s context, or ambitious attempts at fine-tuning on small internal datasets. However, with most of these approaches there’s often no optimization signal, or gradient to move against and progress, if any, involves a good deal of guesswork, trial, and error.

Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) exemplifies this challenge. Many domains, such as medicine, law, and financial services contain specialized terminology that is typically outside the distribution or under-represented in the pretraining for general purpose models. A model trained on everyday speech will struggle with phrases like “orthostatic tachycardia” or specialized homophones that are difficult to disambiguate, such as “ICU” versus “I see you”. Traditional solutions to this issue involve collecting domain-specific audio and ground truth transcriptions (often hand labeled) which can be cost prohibitive. Open source datasets on specialized domains are becoming more common but their volume and variety remain limited, keeping them tangential to many business use cases.

This distribution gap has motivated researchers and practitioners to explore the concept of shallow fusion: combining general-purpose ASR models with domain-specific language models during inference. Rather than requiring extensive retraining, shallow fusion leverages existing domain expertise from an external language model at inference time. While the approach has shown promise in various implementations, the questions I would like to explore in this article are: Can a language model trained on domain-specific text meaningfully improve speech-to-text transcription quality within an adjacent domain? And critically, what are the failure modes associated with this type of integration?

Background & Existing Approaches

The challenge of domain adaptation in ASR has prompted several approaches, each with distinct trade-offs in cost, performance, and implementation complexity. Before diving into my implementation, I’ll examine how the research community has approached this domain mismatch problem and where shallow fusion fits among existing solutions.

Traditional Domain Adaptation

Traditional domain adaptation typically requires collecting domain-specific audio paired with ground truth transcriptions, then fine-tuning pretrained models on this data. While effective, this approach faces significant barriers: domain-specific audio is expensive to collect, transcription labeling is labor-intensive, and the resulting datasets often remain small and brittle compared to the large scale datasets that the base model was trained on. This approach runs the risk of catastrophic forgetting1 where the model loses its general capabilities when adapting to the specific domain.

Context Injection Methods

Context injection methods attempt to bridge the gap by incorporating domain-specific text directly into the model’s context window, essentially “prompting” the ASR system with relevant terminology. However, these approaches offer no optimization signal and rely heavily on trial and error to achieve meaningful improvements. They are also architecture dependent and rely on the decoder’s prompting capacity, which may be limited in models not explicitly designed for such conditioning.

Fusion Techniques

Fusion techniques represent a middle ground, combining predictions from multiple models during inference rather than requiring extensive retraining. The research community has explored three primary variants:

Shallow fusion combines model predictions at inference time via a weighted average of ASR and LM scores, requiring no additional training (Gulcehre et al., 2015).

Deep fusion augments the decoder with a small gating network that learns to merge hidden representations from the ASR and LM while keeping both models frozen (Gulcehre et al., 2015).

Cold fusion builds on the idea of deep fusion but with a key difference: instead of training the ASR model first and then adding a language model later, the ASR model is trained from scratch alongside a fixed, pretrained LM (Sriram et al., 2017).

Shallow fusion’s appeal lies in its simplicity and flexibility, as it requires no additional training of the base ASR model. Instead, you incorporate predictions from an external language model directly at inference time, blending the acoustic model’s view of the audio with the language model’s understanding of domain-specific text. Importantly, the only data needed to build or adapt the external language model is unstructured text, which can be collected far more easily than audio transcriptions.

However, the approach introduces its own challenges. If the language model is weighted too heavily, it may bias transcriptions toward plausible but incorrect tokens; too lightly, and the domain benefits are lost. Tuning the weighting factor for the external model often requires domain-specific adjustment. In addition, shallow fusion increases inference cost since predictions must run through a second model2. These trade-offs make it essential to understand the method’s failure modes before deploying it in practice.

Shallow Fusion: Conceptual Overview

Having established the landscape of existing approaches, we can now detail the implementation of shallow fusion for medical ASR, combining Whisper (our ASR model) with a domain-adapted GPT-2 model (our external language model). However, before going into the specifics let us first build some intuition on the topic by analogy.

Analogy

Consider, for example, a person tasked with transcribing audio from a phone call between a customer and a claims representative at an insurance call center. This transcriber can hear the conversation clearly, but they have very little knowledge of the domain, e.g., the technical issues, procedures, and medical terminology that often come up. Now imagine a second person who has worked in this industry for years and has deep familiarity with the jargon and context, but who is hard of hearing.

In practice, the first person might hear a phrase like “myocardial infarction” but misrecognize or misspell it. The domain expert, although unable to hear the audio, would immediately recognize the intended term and correct the transcript.

Shallow fusion can be thought of as a process of integrating each person’s expertise to offset the errors of one another and bridge modalities the other does not have access to. With this analogy, we can now formally describe this process. In the example below think of \(P_{\text{ASR}}\) as the person listening to the audio and \(P_{\text{LM}}\) as the domain expert that is hard of hearing but deeply understands the context.

Mathematical Formulation

At each decoding step for some audio input, we select the most probable token \(y_{t}\) using information from the Automatic Speech Recognition model (ASR) and the Language Model (LM)

\[ y^* = \arg\max_{y_t}\; \left[ \log P_{\text{ASR}}\!\bigl(y_t \mid x,\, y_{<t}\bigr) \;+\; \lambda\,\log P_{\text{LM}}\!\bigl(y_t \mid y_{<t}\bigr) \right] \]

where:

- \(t\) is the decoding step

(0-based).

- \(y_t\) is the chosen token

at step \(t\) and \(y_{<t}\) are previously generated

tokens.

- \(x\) represents the acoustic

features (e.g., raw audio input).

- \(P_{\text{ASR}}\) depends on

both \(x\) and \(y_{<t}\), while \(P_{\text{LM}}\) depends on \(y_{<t}\) only.

- \(\lambda\) is the weighting factor to determine the language model’s influence.

The idea is that the ASR model understands phonetics and language in a general sense while the LM model understands the specialized domain in its written form, but has no access to the audio signal. Just like in the analogy from earlier by fusing their predictions, we combine phonetic understanding with domain expertise, aiming to improve the quality of transcriptions for domain-specific terms. Without careful integration or synergy between the two, both models can carry major limitations.

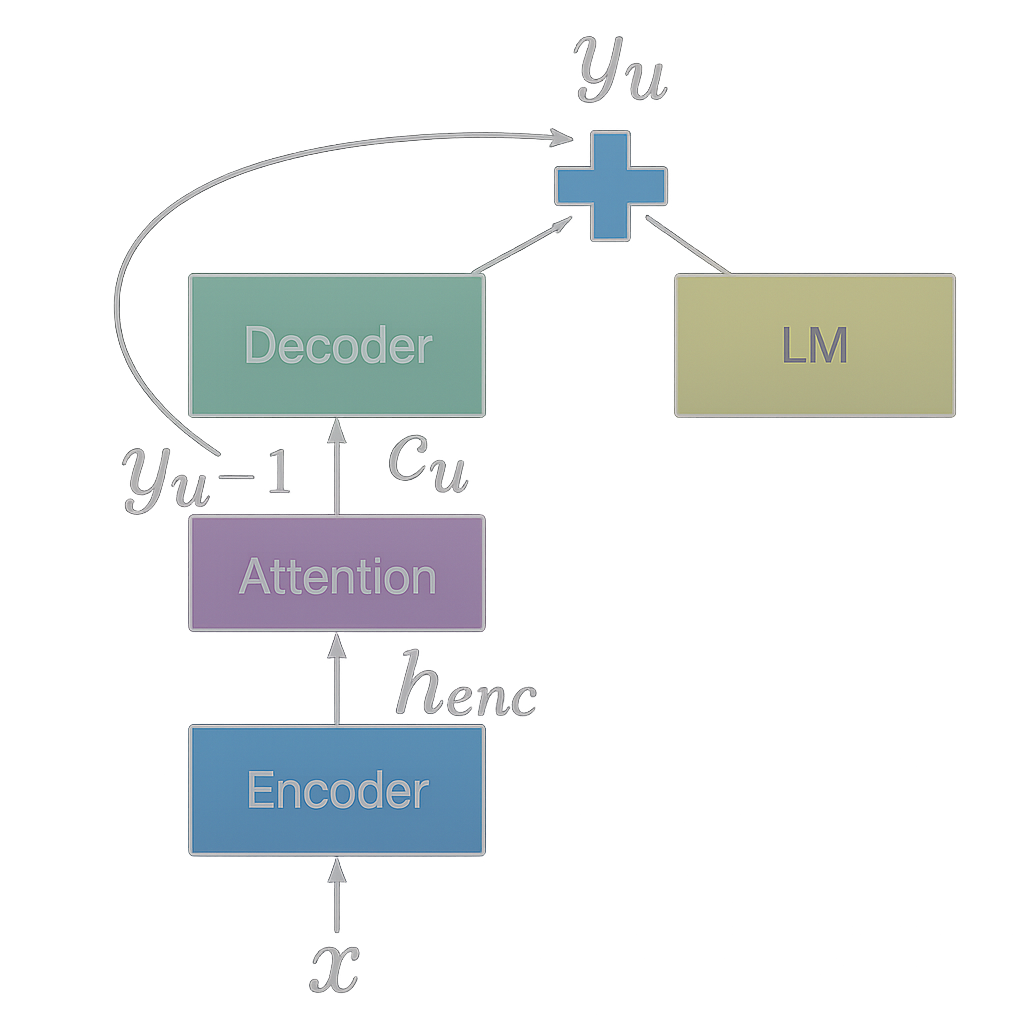

Process Diagram:

Reference: Kannan et

al. (2017)

Reference: Kannan et

al. (2017)

Practical Example

Consider an example where Whisper serves as our listening expert and GPT-2 as our domain-language expert. In practice these models share a tokenizer making the process of integrating their predictions fairly seamless at least for the English version of Whisper (Radford et al., 2022). Now let’s consider a claims call center transcript where an ASR model misinterprets a specialized medical term.

Input Audio (Ground Truth):

“The procedure was medically necessary for the treatment of

claimant’s Tetralogy of Fallot.”✔️

Whisper Initial Output:

“The procedure was medically necessary for the treatment of

claimant’s Tetralogy of below.”🚫

Step-by-Step Fusion Process

1. Whisper Initial Decoding:

Whisper produces log probabilites at each step:

- Token: “The” -> high confidence

- Token: “procedure” -> high confidence

- Token: “claimant” -> high confidence

- Token: “’s” -> high confidence

- At the final subword, Whisper may exhibit uncertainty, spreading probabilities across candidates: “below”, “follow”, “Fallot”

2. Domain GPT-2 Predictions:

At the ambiguous decoding step in “The procedure was medically

necessary for the treatment of claimant’s Tetralogy of ____”, each

model produces different log probabilities:

| Next Token | Whisper Log Probs | GPT-2 Log Probs |

|---|---|---|

| Fallot | –1.8 | –0.3 |

| below | –1.0 | –5.0 |

| follow | –3.5 | –3.8 |

Note: GPT-2, which has been fine tuned on medical literature, strongly favors the correct token (produces log probabilities closer to 0 for Fallot) while Whisper, which had minimal access to medical terminology, assigns it a much lower likelihood (log probabilities that are more negative).

3. Shallow Fusion (Combining Log Probabilities):

Fusion Equation:

We combine each model’s log probabilites using a weighted sum in the following way:

\[ \log P_{\text{combined}}(y_t) = \log P_{\text{Whisper}}(y_t \mid x, y_{<t}) + \lambda \log P_{\text{GPT2}}(y_t \mid y_{<t}) \]

Example:

| Next Token | Whisper Score | GPT-2 Score | Combined Score (λ = 0.2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fallot | –1.8 | –0.3 | –1.8 + 0.2 × (–0.3) = –1.86 |

| below | –1.0 | –5.0 | –1.0 + 0.2 × (–5.0) = –2.0 |

| follow | –3.5 | –3.8 | –3.5 + 0.2 × (–3.8) = –4.26 |

Note: These values are illustrative. In practice, rare medical terms may be split across multiple tokens, but the principle remains the same, the domain model’s confidence helps disambiguate uncertain acoustic predictions.

Final Corrected Output:

Since “Fallot” now has the highest combined score the final output

reads: “The procedure was medically necessary for the treatment of

claimant’s Tetralogy of Fallot.”✔️

This illustrates how domain-aware shallow fusion could potentially improve ASR output in specialized contexts.

Experimental Setup

Model Selection and Preparation

For this implementation, I chose Whisper as the base ASR model due to its strong general-purpose performance and GPT-2 as the domain-specific language model. The external models selected for this fusion process were GPT-2 small, medium, and large. The reason for selecting these models was partly due to the shared tokenizer/vocabulary they have with Whisper’s decoder. The shared vocabulary means we do not have to learn a mapping from one model’s vocabulary to another. While Bio-GPT represents an existing medical language model, it uses a different tokenizer that would require learning a mapping function between tokenization schemes. To avoid potential errors and implementation complexity, I opted to train custom GPT-2 variants on medical data thus preserving Whisper’s tokenizer compatibility.

Training Domain-Specific Language Models

To adapt an external language model to the medical domain, the PubMed dataset was used. Multiple versions of GPT-2 were tuned on roughly 3.63 billion tokens from PubMed abstracts. Three GPT-2 variants were trained to create the following domain-adapted language models:

- GPT-2 Small (124M parameters)

- GPT-2 Medium (355M parameters)

- GPT-2 Large (774M parameters)

The models were trained using standard autoregressive language modeling objectives on this large corpus of medical abstracts. Retaining Whisper’s tokenizer ensured seamless fusion, eliminating any need for token mapping or vocabulary alignment.

Training pipeline and tuned models:

Fusion Pipeline Architecture

The fusion pipeline operates selectively on relevant tokens only. Whisper contains special task-related tokens (language identifiers, task specifiers, timestamps) that are outside the scope of GPT-2’s vocabulary and training domain. However, for the English transcription task, Whisper should not emit these special tokens during normal operation, making this a non-issue in practice.

The implementation performs fusion by:

- Running Whisper’s encoder to generate audio features

- At each decoding step, computing logit distributions from both Whisper’s decoder and the domain-adapted GPT-2

- Combining log probs for shared tokens using the weighted sum formulation described earlier

- Selecting tokens based on the fused probability distribution

Evaluation Framework

Dataset Generation: Testing was conducted on 358 synthetic radiology dictations (each under 30 seconds) generated by two large language models. Texts were produced by GPT-5 (Thinking) and Claude 4.1 using the following prompt:

| Prompt |

|---|

| Please generate 150 unique radiology report dictations.

Dictations must contain realistic medical terminology with correct usage and spelling. Additionally, these sentences must be text to speech friendly. Data should be provided in a markdown cell and formatted as such: { “radiology_dictations”: [ {“text”: “…”}, …, {“text”: “…”} ] } |

Both models exceeded the target, yielding 358 unique

sequences. Each sequence was synthesized to mono WAV format using

OpenAI’s text-to-speech system (TTS) at a constant sample rate,

with no added noise or reverberation.

Dataset Limitations: Results are based on LLM-written text rendered with clean TTS audio, which under-represents real dictation variability (accents, disfluencies, noise); gains may not generalize to clinical speech without proper validation (see future directions section).

Evaluation Methodology: The primary evaluation metric was Word Error Rate (WER)3, which measures the percentage of incorrectly transcribed words. Testing compared transcriptions from:

- Whisper-only baseline

- Shallow fusion with vanilla GPT-2 models (small, medium)

- Shallow fusion with GPT-2 models fine-tuned on PubMed abstracts (small, medium)

- Various λ weighting values to optimize fusion performance

The comparison between vanilla and PubMed-tuned GPT-2 models tests whether domain-specific language modeling provides additional benefits for medical transcription accuracy.

Results & Analysis

Overall Performance

Shallow fusion’s effectiveness depends critically on domain expertise. Testing with both medical and generic language models reveals a striking divergence:

Figure 2: Word error rates across fusion weights (λ) in preliminary testing. Medical GPT-2 (green) reduced WER below baseline while generic GPT-2 (red) increased it in this synthetic evaluation. Interactive hover for details

The medical models achieved optimal performance at λ = 0.24-0.30, with the small configuration reducing WER from 6.86% to 6.28% (8.5% relative improvement) and the medium configuration from 5.16% to 4.80% (7.0% relative improvement). In contrast, generic GPT-2 models consistently increased error rates, suggesting that the improvement comes from a medically-adapted language model as opposed to a generic one. These results align with prior work, Kannan et al. (2017), who reported a 9.1% relative WER reduction on Google Voice Search using shallow fusion. Overall, The medical models excel at correcting specialized terminology like “scapholunate” from “scaffolunate,” while generic models introduce errors by biasing transcriptions toward everyday language.

Hyperparameter Sensitivity (λ / Lambda Weight)

The fusion weight λ controls the balance between acoustic and language model predictions. Testing λ values from 0.03 to 0.36 revealed consistent patterns across model sizes:

Table 1: WER Performance Across Fusion Weights

| Configuration | Baseline WER | Optimal λ | Best WER | Relative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whisper Small + Medical GPT-2 Small |

6.86% | 0.24 | 6.28% | 8.5% |

| Whisper Medium + Medical GPT-2 Medium |

5.16% | 0.30 | 4.80% | 7.0% |

Performance degrades at extreme λ values, when too low

fusion provides minimal domain benefit, while too high (> 0.33)

causes the language model to override valid acoustic evidence. The

optimal range (0.24-0.30) suggests a consistent balance point

where domain knowledge enhances without overwhelming acoustic

information.

Statistical Significance

The fused system and original Whisper only system were tested on 358 of the same audio clips.

For the small model, overall errors fell from 6.86% to 6.28% (8.5% relative reduction). A permutation test4 suggests a difference this size would happen by chance about 1 in 81 times if testing only for improvement (one-sided p = 0.012). With 44 improved utterances versus 21 degraded ones, this pattern is consistent with a modest real effect on this set.

For the medium model, overall errors went from 5.16% to 4.80% (7.0% relative reduction). The permutation test suggests a difference this size could occur about 1 in 30 times if testing only for improvement (one-sided p = 0.034). With 30 improvements versus 14 degradations, this is promising but test would benefit from more data.

Bottom line: Shallow fusion results show modest, yet consistent error reductions on this dataset where fusion improvements are statistically significant. However, more data, ideally real clinical dictations, would make the conclusion more definitive.

Error Pattern Analysis and Failure Modes

While the synthetic evaluation showed promising patterns, analysis revealed specific failure modes that illuminate the method’s limitations:

1. Abbreviation Expansion Mismatches

The fusion system frequently “over-corrected” spoken abbreviations

into their formal written equivalents. For example:

- Audio: “centimeters” -> Whisper: “centimeters” -> Fused output: “cm”

- This reflects the domain language model’s bias toward written medical documentation style

2. Punctuation Insertion

The GPT-2 model, trained on formatted medical abstracts,

introduced punctuation that wasn’t present in the spoken audio.

This created a stylistic mismatch between transcribed speech and

formal written medical language, with inappropriate hyphenation of

compound terms being particularly prominent (e.g.,

“hydronephrosis” -> “hydro-nephrosis”).

3. Premature Termination and Incomplete

Transcripts

When λ (the LM weight) was set too high, beam search decoding

often produced incomplete transcripts. Chorowski & Jaitly

(2016) reported that external LMs can cause seq2seq systems to

skip words or drop parts of an utterance during decoding, unless a

coverage term is added to the beam search criterion. In this

experiment, higher λ coupled with wide beam searches similarly led

to premature terminations, with the LM assigning high probability

to end-of-sequence tokens once a transcript appeared semantically

complete, even while audio continued.

Domain-Specific Improvements

The fusion approach’s benefits were concentrated almost exclusively in medical terminology recognition. Examples of successful corrections included:

- Complex pharmaceutical names

- Anatomical terminology

- Rare disease names and medical conditions

- Procedural and diagnostic terminology

Standard conversational language showed minimal improvement, suggesting that benefits in this synthetic evaluation may derive from domain expertise rather than general language modeling enhancement.

Reflection and Future Directions

Addressing Current Limitations

The experimental results highlight several areas for improvement that point toward promising future research directions:

Real-World Dataset Validation: The synthetic evaluation dataset, while useful for proof-of-concept demonstration, limits the generalizability of these findings. Future work should incorporate authentic clinical dictations such as the Shaip Physician Dictation Dataset, which requires Databricks account permissions. Real clinical speech presents challenges absent in synthetic data: background noise, speaker variations, interruptions, and the full complexity of clinical communication patterns.

Coverage Penalty: The current implementation does not make use of a coverage penalty to address premature sequence terminations. This penalty term measures how much of the audio the model actually attended to and candidates that skip large stretches are penalized, while transcripts that cover the whole utterance are preferred. This strategy follows Chorowski & Jaitly (2016) and Kannan et al. (2017) and can be incorporated during generation.

Learned Gating Mechanisms: The static λ weighting approach represents a significant limitation. A more sophisticated system would dynamically adjust the influence of the external language model based on acoustic confidence and contextual cues. When Whisper exhibits high confidence in its predictions, the domain model should have minimal influence. Conversely, during periods of acoustic uncertainty, particularly around medical terminology, the fusion weight should increase. Implementing this would likely involve training a small gating network that learns to predict optimal λ values given acoustic features and partial transcript context.

Advanced Fusion Architectures: Beyond shallow fusion, deep fusion and cold fusion approaches warrant investigation. Deep fusion could learn more sophisticated integration by combining hidden states and tuning a task-specific fusion function. Cold fusion could be explored by integrating the domain language model during Whisper’s training process, though this would require more substantial computational resources and training data.

Broader Implications

This work connects to several important trends in contemporary AI development:

Ensemble and Mixture-of-Experts Architectures: Shallow fusion represents a simple form of ensemble modeling, where specialized models contribute their expertise to improve overall performance. This aligns with the broader trend toward Mixture-of-Experts architectures that dynamically route inputs to specialized sub-networks.

Multimodal Integration Challenges: The fusion of acoustic and textual information highlights fundamental challenges in multimodal AI systems. Different modalities often have distinct statistical properties and optimal representations, requiring careful integration strategies.

Domain Adaptation Strategies: As AI systems deploy across increasingly specialized domains, the tension between general capability and domain expertise becomes more pronounced. Shallow fusion offers one approach to leveraging domain-specific knowledge without extensive retraining of large general-purpose models.

Conclusion

This exploration of shallow fusion for medical ASR demonstrates both the promise and limitations of combining general-purpose models with domain-specific expertise. The key insight is that each model type hits distinct “data walls”:

Whisper (Generalist Model) excels at acoustic-to-text mapping and handles diverse speakers, accents, and recording conditions effectively. However, its broad training distribution means medical terminology remains under-represented, leading to systematic errors on specialized vocabulary despite strong general performance.

GPT-2 (Domain Specialist), trained on PubMed abstracts, develops rich representations of medical terminology and context through self-supervised learning on abundant textual data. However, it remains completely blind to acoustic signals and exhibits biases toward formal written language rather than conversational speech patterns.

The preliminary synthetic evaluation, showing up to 8.5% WER reduction, suggests shallow fusion may have potential for improvement, though further validation on clinical data is needed. Additionally, the failure modes (abbreviation mismatches, punctuation insertion, and premature terminations) reveal the challenges of bridging modalities with different statistical properties and stylistic conventions.

The observed improvements appeared concentrated on medical terminology recognition, suggesting that the benefits may derive from genuine domain expertise rather than general language modeling improvements. This specificity, while limiting the approach’s broad applicability, makes it particularly valuable for specialized transcription applications where domain terminology accuracy is critical.

Future work towards learned gating mechanisms, advanced fusion architectures, and validation on authentic clinical datasets will help address current limitations. More broadly, this work illustrates the ongoing evolution of AI system architectures from monolithic models toward composite systems that combine specialized expertise, a trend likely to accelerate as AI deployment expands across diverse professional domains.

Resources

- On Using

Monolingual Corpora in Neural Machine Translation — Gulcehre

et al., 2015

- Cold Fusion:

Training Seq2Seq Models Together with Language Models — Sriram

et al., 2017

- Towards Better

Decoding and Language Model Integration in Sequence-to-Sequence

Models — Chorowski & Jaitly, 2016

- Analysis of

Incorporating an External Language Model… — Kannan et al.,

2017

- Robust Speech

Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision — Radford et al.,

2022

- Language

Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners — OpenAI,

2019

- Language Models are Few-Shot Learners — Brown et al., 2020

Catastrophic forgetting occurs when a neural network loses previously learned information upon learning new tasks or data.

Several variations exist to reduce the inference cost of shallow fusion, including N-best rescoring (applying the LM only to candidate transcripts) and using smaller or distilled domain LMs.

Word Error Rate (WER) is the standard metric for evaluating ASR systems, calculated as the minimum number of word-level edits (insertions, deletions, substitutions) required to transform the hypothesis into the reference, divided by the total number of words in the reference.

A shuffle test (permutation test) is a nonparametric significance test where labels (baseline vs. fused) are randomly swapped to see how often a difference as large as the observed one would arise by chance.